Recommendations for a System Update

Download the policy paper as PDF

Intelligence services around the world are driving the evolution of surveillance technology – a rapid, bold, and multi-faceted development. Many countries will run the risk of conducting irrelevant intelligence oversight processes if they fail to incorporate supervisory technology more systematically. The growing volumes of data used in the intelligence sector overwhelm the de facto guarantees of legal safeguards and effective oversight. Modern data analysis entails numerous risks in terms of data abuse and circumventing legal requirements. A lack of up-to-date tools, resources, and technical expertise serves to further undermine effective oversight.

Oversight bodies need an update. They need to adopt tech-enabled instruments to respond to the technological advancements driving the intelligence field. Since key European nations are currently preparing new intelligence reforms, we hope that oversight bodies will embrace a paradigm shift from paper-driven to data-driven reviews.

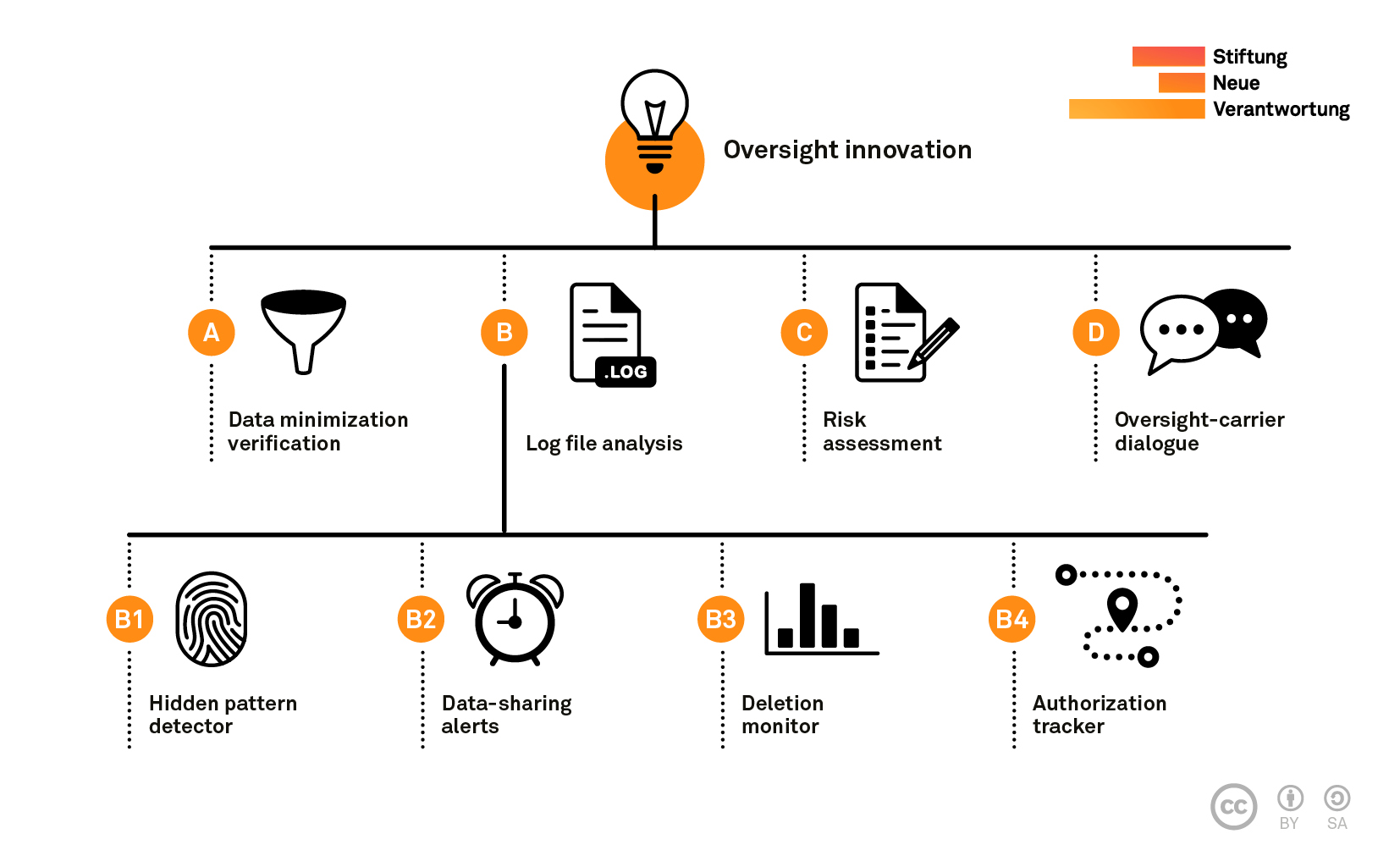

To advance this process, we would like to propose seven tools for data-driven intelligence oversight that should become part of a reform agenda across Europe. Each tool represents a viable solution to a concrete oversight challenge. Many build upon direct access to operational systems, which enables oversight bodies to conduct unannounced checks as well as (semi-)automated audits on intelligence agencies’ data processing. Some of our proposed tools are already being used by intelligence oversight pioneers, while others have been borrowed from good practices in other sectors, such as financial supervision and IT security. The following table summarizes the pressing challenges facing intelligence oversight, coupled with innovations that we feel could effectively meet these challenges.

| Oversight Challenges | Corresponding Tools |

|---|---|

| Mystic filter technology: Some intelligence legislation mandates greater data protection safeguards for certain groups. To enforce these types of requirements, agencies carry out data minimization processes, which are critical for legal compliance. However, these filters are rarely submitted to independent checks for accuracy and reliability. | (A) Data minimization verification Direct access to the services’ stored data enables oversight bodies to test the accuracy of data minimization. This involves scanning the databases with search programs for identifiers (such as phone numbers) that should not be detectable in the filtered data. |

| Abusive database queries: Cases of illegal and inappropriate intelligence database use can occur when there are insufficient protections in place. | (B1) Hidden pattern detector Data analysis software for tracking and visualizing the use of databases. Oversight bodies review log files for potentially suspicious patterns. |

| Poorly monitored intelligence cooperation: Most oversight bodies lack review mechanisms for ascertaining whether and how national agencies share data with foreign services. Accordingly, these bodies have no control over the use of data that has been shared. | (B2) Data-sharing alerts Automated notifications flag critical data sharing arrangements for in-depth review by oversight bodies. |

| Enforcing retention limits: When analysts or system administrators merge data from sources that do not have the same retention periods, data may remain stored in the databases concerned even after the retention limits have lapsed. | (B3) Deletion monitor Deletion activities are recorded in well-structured log files so that oversight bodies can detect outliers in the statistical patterns contained in deletion records. |

| Trace the use of warrants: Oversight bodies struggle to keep abreast of the large volumes of requests for surveillance measures. They often lack comprehensive digital trails that would make it possible to review the trajectory of authorized data collection and subsequent data use. | (B4) Authorization tracker Digital documentation of all warrants and approval decisions allows authorizing judges to detect the simultaneous use of multiple surveillance measures, assess the necessity of new requests and find boilerplate justifications in applications. |

| Scarce resources: Oversight bodies struggle to systematically decide how to allocate their limited resources effectively and plan their work accordingly. | (C) Risk assessment Independent reviewers calculate detailed risk scores for each intelligence systems within their mandate to create a verifiable evidence base for prioritizing oversight tasks. |

| Opaque agency interaction with private intermediaries: Avoiding over-collection at interception points is critical for preventing rights violations. Oversight bodies do not know enough about this – how can they spot errors such as incorrectly installed bearers? | (D) Oversight-carrier dialogues Systematic exchanges between industry players and oversight bodies enable reviewers to track the implementation of data collection. Combined with intermediaries’ obligation to report errors, this permits to detect workarounds that undermine legal requirements. |

We invite policymakers, intelligence agencies, and oversight bodies to discuss these tools and develop context-specific strategies for data-driven intelligence oversight. In order to successfully implement these tools, we advise oversight bodies not to regard them as substitutes for traditional oversight mechanisms; instead, they should be viewed as necessary additions to existing toolkits and inspection processes.

The hard work of improving oversight will require more than amending existing laws. There has been an overreliance on purely legal solutions to tech-inflicted challenges for too long. This report shows that legal requirements cannot be effectively enforced if the corresponding practical measures are not taken. A concerted effort is thus needed to identify better instruments that complement the legal frameworks and establish accountability.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation – Project Number 396819157) and by a grant from the Foundation Open Society Institute in cooperation with the Information Program of the Open Society Foundations (Grant Number OR2018 – 45772). The authors are particularly grateful to the members of the European Intelligence Oversight Network (see list of focus group participants in the annex) for their in-depth, constructive feedback on an earlier version of this report. In addition, we would like to thank Giles Herdale, Eric Kind, Jan-Peter Kleinhans, Jörg Pohle, and Félix Tréguer for their valuable comments. We are also grateful for the editorial assistance provided by Sebastian Kostadinov. The authors are solely responsible for the contents of this paper, and the views expressed therein do not necessarily reflect those of the commentators and reviewers.